Izquierdo et al., 2022, Cancer Discov. DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0930

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway alterations are commonly found in childhood cancer, particularly brain tumors, and especially low- and high-grade gliomas. Although targeted agents against the MAPK pathway (inhibitors targeting BRAF – vemurafenib, dabrafenib and MEK – trametinib, selumetinib, cobimetinib) have become an important initial success story in the field of precision oncology, they are frequently associated with the emergence of resistance and treatment failure.

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) remains one of the most intractable pediatric malignancies, characterised by a dismal prognosis and resistance to conventional therapies. The tumour’s anatomical location and diffuse infiltration preclude surgical intervention, while radiotherapy provides only transient benefit. Methylation and genomic profiling has revealed DIPG molecular heterogeneity with recurrent somatic mutations, including histone H3 alterations (H3K27M), TP53 mutations, and alterations in growth factor and mitogen-activated signaling cascades. Among these, aberrations in the MAPK pathway have emerged as potentially actionable drivers.

Resistance to single agents mentioned above often were thought to be mediated by reactivation of MAPK through amplification or splice variants in BRAF, mutations in the upstream oncogene NRAS, or the downstream kinase MEK1 (MAP2K1), and PI3K–PTEN–AKT upregulation. Therefore, this led to the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors in clinical trials, but soon acquired resistance was also observed with identification of MEK1 and MEK2 (MAP2K2) mutations as two of the main mechanisms. However, these combinations have not yet been explored in the context of DIPG.

Utilising patient-derived models (in vitro and in vivo) from phase II co-clinical trial of patients with DIPG from United Kingdom enrolled in BIOMEDE, Izquierdo et al. investigated specific genetic dependencies associated with response to trametinib in vitro, explored mechanisms of acquired resistance that emerge to single-agent targeted therapy, and presented rational drug combinations that may circumvent this in future clinical trials.

[MAPK alterations confer in vitro sensitivity to trametinib in DIPG models from coclinical trial]

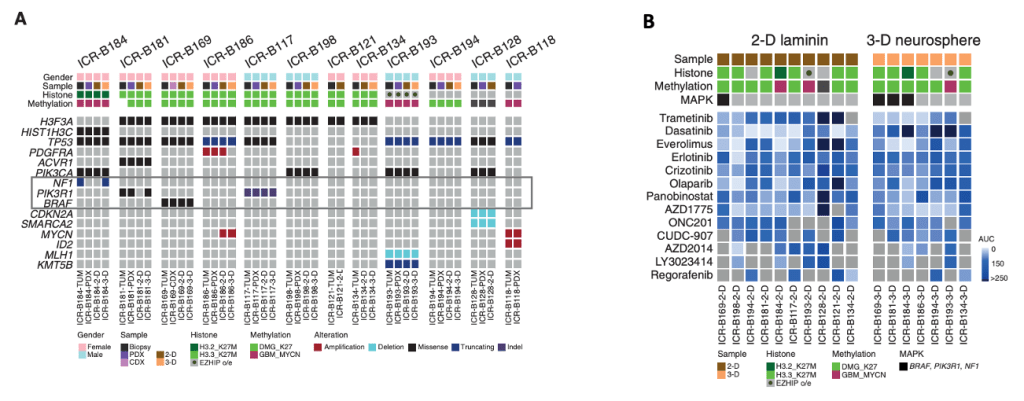

Clinicopathologic and molecular annotations of patient-derived models and tumor biopsy specimens.

BIOMEDE (NCT02233049) is a phase II, biopsy-driven clinical trial in patients with DIPG with randomization of stratification between dasatinib, erlotinib, and everolimus. From UK patients, Izquierdo and her colleagues generated patient-derived in vitro and in vivo models from biopsy material excess to trial inclusion.

(A) Oncoprint representation of an integrated annotation of single-nucleotide variants, DNA copy number changes, and structural variants for patient-derived models and tumor biopsy specimens.

(B) Drug sensitivities in the mini-screens carried out on cells grown under 2-D and 3-D conditions (seventeen established cultures from 11 patients), visualized by heat map of normalized AUC values.

They observed that MAPK-altered DIPG cells displayed increased sensitivity to the MEK inhibitor Trametinib, while MAPK-wild-type lines were largely unresponsive. These data provided initial evidence that MEK inhibition might serve as a precision therapeutic strategy in this molecular subset of DIPG.

However, this preclinical sensitivity did not uniformly translate into durable responses in vivo. A BRAF G469V DIPG patient treated with Trametinib showed limited clinical benefit. Similarly, xenografts harboring MAPK alterations demonstrated only transient responses. This prompted a deeper investigation into the mechanisms underlying therapeutic resistance.

[Resistance mechanisms from persister clones to genetic reprogramming]

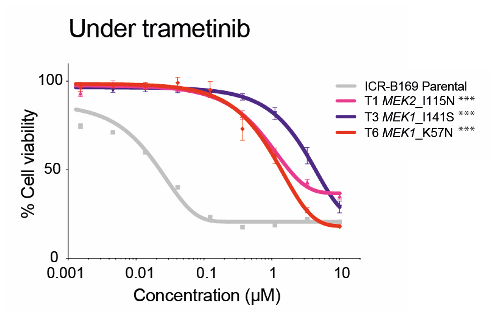

To model acquired resistance, the authors subjected a BRAF-mutant DIPG cell line (ICR-B169) to either an exponentially increasing dose of inhibitor over time (approach 1) or a constant IC80 dose (approach 2).

(LEFT) Dose-response curves for trametinib tested against ICR-B169 parental cells (gray) and resistant clones T1 (MEK2I115N, pink), T3 (MEK1I141S, purple), and T6 (MEK1K57N, red) after 7 to 9 months of exposure to the inhibitor.

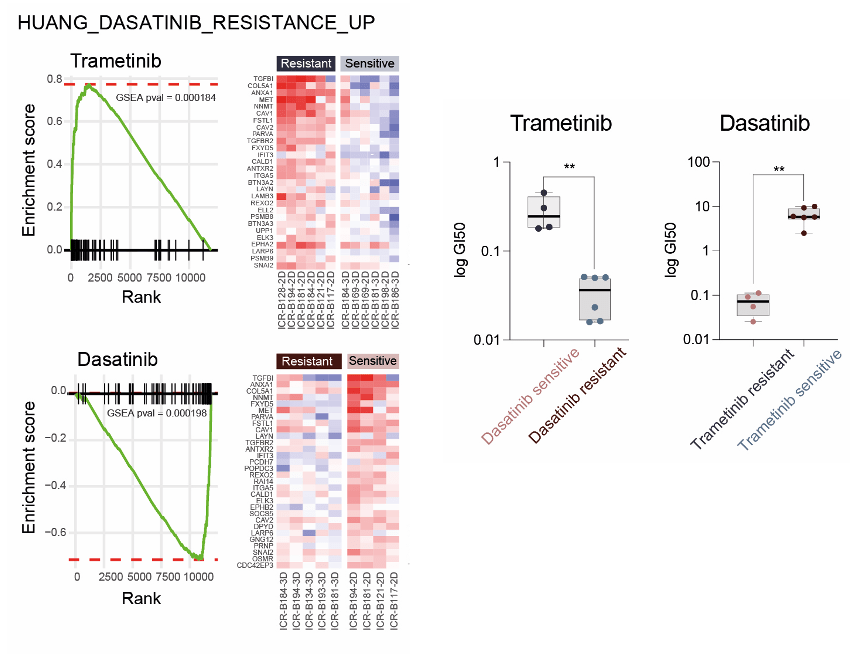

(Middle) GSEA enrichment plots for the signature HUANG_DASATINIB_RESISTANCE_UP in primary patient-derived cultures separated by trametinib (top) or dasatinib (bottom) sensitivity status. The curves show the enrichment score on the y-axis and the rank list metric on the x-axis. Alongside are heat map representations of expression of significantly differentially expressed genes in the signature in all trametinib- or dasatinib-resistant versus sensitive cell cultures.

(Right) Box plot of dasatinib GI50 values (log scale, y-axis) for primary patient-derived cultures separated by trametinib sensitivity status. / Box plot of trametinib GI50 values (log scale, y-axis) for primary patient-derived cultures separated by dasatinib sensitivity status. **, P < 0.001, t test.

In order to investigate if resistance was selected from pre-existing tumor subclones or was acquired in vitro in response to Trametinib treatment and to explore the mechanism by which mutations in MEK1/2 confer resistance to trametinib in DIPG cells, Izquierdo et al. performed gene expression profiling by RNA sequencing and total and phospho-proteome analysis by LC/MS-MS. They identified the intersection of the shared most differentially upregulated or downregulated genes, proteins, and phospho-sites between the three Trametinib resistant clones T1, T3, and T6 – resulting in integrated signature of coordinately regulated signaling changes induced by MEK1/2 mutation in response to challenge by Trametinib treatment.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of this integrated signature showed a high degree of concordance between the clones and included activation of numerous processes involved with cytoskeleton reorganization, cell migration, cell polarization, and cell matrix remodeling, as well as depletion of neural and oligodendrocyte markers. Most importantly, they identified a significant enrichment of a gene signature indicative of sensitivity of cancer cells lines to Dasatinib, HUANG_DASATINIB_RESISTANCE_UP.

[Combinatorial Approaches for Overcoming Trametinib Resistance in DIPG]

Building on this observation, the authors hypothesised that SRC family kinases, implicated in the mesenchymal and migratory phenotype of resistant clones, could serve as co-targets to suppress adaptive escape mechanisms.

They evaluated the efficacy of combining trametinib with dasatinib, a multi-kinase inhibitor known to inhibit SRC family, BCR-ABL, c-KIT, PDGFRb, etc. This combination demonstrated synergistic activity across both trametinib-resistant MAPK-altered DIPG models, leading to marked suppression of tumour cell viability, proliferation, and invasion. Notably, in ex vivo brain-slice cultures, which preserve the three-dimensional architecture and microenvironmental context of the brainstem, the dual therapy significantly reduced infiltrative tumour growth—an essential feature of DIPG pathobiology. Mechanistically, dasatinib appeared to antagonise the mesenchymal transcriptional program induced by prolonged MEK inhibition, thereby restoring sensitivity to trametinib.

These findings therefore underscore the therapeutic potential of upfront dual inhibition of MEK and SRC as a rational strategy to overcome both intrinsic and acquired resistance in MAPK-driven DIPG.

—

[Discussion]

Trametinib is a selective reversible inhibitor of MEK1/2 that binds to the allosteric pocket of MEK. The study identifies biomarkers of response to trametinib, which involves: 1) multiple nodes of the MAPK signaling pathway, 2) PIK3R1 N564D, 3) NF1 I1824S, 4) BRAF G469V. These suggest a possible rationale for the use of trametinib in DIPG. TRAM-01, an on-going phase II clinical trial (NCT03363217), explores the use of trametinib in pediatric gliomas harbouring MAPK alterations independently of the tumor entity.

PIK3R1 N564D (ICR-B181) is an oncogenic hotspot mutation (PIK3R1: considered tumor suppressor gene) lying within the regulatory subunit of PI3K, known to promote cell survival in vitro and oncogenesis in vivo. This mutation results in loss of function, which is predicted to destabilise protein interaction, which may affect tumor suppressive function. Such PIK3R1 oncogenic mutations have been shown to activate the MAPK pathway and exhibit sensitivity to MAPK inhibitors.

NF1 I1824S (ICR-B184) lies in the neurofibromin chain and the lipid binding region, which may affect the protein folding and the tumor suppressor gene function. The efficacy of MEK inhibitors has previously been shown in NF1-deficient glioblastoma cell lines. Overall, trametinib sensitivity was only identified in the mutant cultures, which also had higher basal levels of MAPK pathway activation. This possibly supports the hypothesis that these mutations were responsible for the observed trametinib efficacy in vitro.

BRAF G469V is a class II BRAF mutation within the protein kinase domain, resulting in increased kinase activity and downstream MEK and ERK activation. BRAF class II mutations have constitutively activated in BFRA dimers independent of RAS activation, and BRAF G469V has been shown to confer sensitivity to trametinib in melanoma and lung cancer. Despite this, targeting this mutation with MEK inhibitor in DIPG as a single agent in vivo failed to elicit a significant response. There are also concerns over the emergence of resistance to MEK inhibition. We showed the acquisition of MEK1/2 mutation in DIPG cells through continuous trametinib exposure experiments, resulting in pathway reactivation and the irreversible resistance to trametinib.

MEK1 and MEK2 exhibit 85% peptide sequence homology. MEK1 K57N lies on the helix A domain within the N-terminal negative regulatory region and is associated with high levels of RAF-regulated activation of ERK signaling. Interestingly, MEK1 K57N has been attributed to cause resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors in vitro and in patients with melanoma. In our resistant models, the presence of the MEK1/2 mutations resulted in shift of 2 to 3 orders of magnitude of trametinib concentration required to inhibit MAPK signaling.

Notably, using integrated RNA-seq and phospho/total proteomics, a drift from a proneural to mesenchymal phenotype was observed in the MEK1/2-mutant resistant clones, a feature also observed in patient-derived models inherently insensitive to trametinib. This has been broadly reported as a hallmark of metastasis and resistance to multitherapy in cancer. In particular, glioma-initiating clones displaying drug resistance and radioresistance have been previously linked to a proneural-mesenchymal transition.

In our models, this was also accompanied by a reciprocal sensitivity of the trametinib-resistant DIPG cells to the multi-kinase inhibitor Dasatinib. In this context, phosphor-kinase profiling highlighted Src family kinases as the likely mediators of this response rather than PDGFR signaling. In other cancers, Dasatinib has been reported to overcome mesenchymal transition associated resistance to erlotinib in non-small cell lung cancers. In DIPG, the combined use of Dasatinib and trametinib showed a high degree of synergy in vitro and ex vivo brain slices and may represent a novel combinatorial approach in this disease. Cobimetinib and Binimetinib are more clinically relevant brain-penetrant MEK inhibitors – results also consistant. It remains to be explored how best these combinations could be translated clinically in order to prevent or overcome resistance to MEK inhibitors. One method may be an assessment of an intermittent multi-therapy regimen and mathematical modelling.

Leave a comment