Dagogo-Jack and Shaw, Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15, 81-94 (2018)

One of the biggest challenges in precision oncology is the dynamic and multifaceted nature of tumour heterogeneity. Dagogo‑Jack and Shaw articulate how intra- and intertumoural heterogeneity drive resistance to targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and even cytotoxic agents.

- Intertumoral heterogeneity: Heterogeneity between patients harbouring tumors of the same histological type which often results from germline genetic variations, differences in somatic mutation profile, and environmental factors.

- Intratumoral Heterogeneity: Heterogeneity among the tumor cells of a single patient.

- spatial heterogeneity; uneven distribution of genetically diverse tumor subpopulations across different disease sites or within a single disease site of a tumor.

- temporal heterogeneity: The dynamic variations in the genetic diversity of an individual tumor over time).

This blog post synthesises key concepts from their review, tracing the biological underpinnings of tumour diversity, the technological advances that are reshaping how we detect and monitor tumor heterogeneity, and emerging strategies to overcome therapy resistance.

[Understanding intratumoral heterogeneity: causes]

Whilst tumor heterogeneity exists both spatially and temporally, this diversity arises from a combination of key drivers: genomic instability, clonal evolution, and tumor microenvironmental pressures.

- Genomic instability

Genomic instability can range from a single-base substitution to a whole genome doublings. This might result from aberrations in endogenous processes (e.g. DNA replications and/or repair errors, or oxidative stress) and exogenous mutagens (e.g. UV radiation or tobacco smoke).

Few examples include:

– Microsatellite instability (MSI) owing to deficiencies in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) increases somatic mutation burden of subset of colorectal cancers (CRCs)

– Enrichment of C>A transversions are related to smoking-related lung cancers and C>T transitions are prone to MMR-deficient CRCs.

– Exposure to chemotherapy might also increase the mutational spectrum of tumor and create genomic instability:

*APOBEC mutational signature (DNA editing enzyme)

= Characterised by C>T and C>G mutations at TpC sites – are enriched in the later stages of tumor development and becomes more prevalent after exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

E.g. Increased APOBEC3B expression and lower disease free survival correlate in myeloma and oestrogen receptor positive breast cancers.

DNA cytosine deamination resulting from upregulation of DNA dC -> dU editing enzyme APOBEC3B was shown to contribute to mutagenesis in approximately half of all human cancers.

In brain tumors, genomic instability results from chromosome-level changes that lead to gain or losses of whole-genome segments rather than point mutations (chromosomal instability) - The clonal evolution/ selection hypothesis

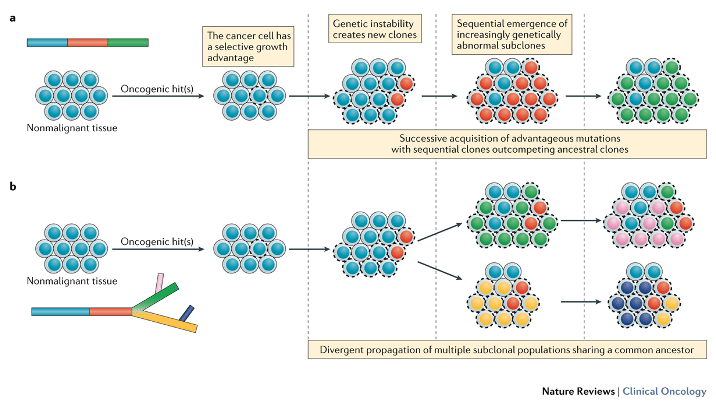

Various models have been proposed to explain how clonal diversity is generated and maintained. This model was first introduced by Peter Nowell in 1976, which is based on the hypothesis that tumor initiation occurs in a stochastic manner, beginning with an induced change in a previously nonmalignant cell that confers a selective growth advantage and leads to neoplastic proliferation.

Subsequently, the genomic instability of the expanding tumor population creates additional genetic diversity that is subjected to evolutionary selection pressures, resulting in the sequential emergence of increasingly genetically abnormal and heterogeneous subpopulations.

Figure 2 . Distinguishing between linear and branched tumour evolution.

Dagogo-Jack, I. & Shaw, A. T. (2017) Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies.

Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166

Two major patterns of evolution exist within the context of the clonal evolution/selection framework. a | In the linear evolution model, sequential genetic alterations confer a fitness advantage such that successive generations (red, followed by green) are able to outcompete the preceding clones (blue), which lack this fitness advantage. Surviving dominant clones (green) harbour the ancestral mutations. b | In the branched evolution model, multiple genetically distinct populations (green, pink, yellow, purple) can emerge from a common ancestral clone (red), with certain subclonal populations diverging from the common ancestor before others.

[Spectrum of tumor heterogeneity]

i) Spatial Heterogeneity

Uneven distribution of genetically diverse tumor subpopulations across different sites, and sometimes within a tumor in a single anatomical location.

ii) Temoral Heterogeneity

The dynamic variation in the genetic diversity of a tumor over time. Data from studies employing serial biopsy sampling to characterise the evolution of tumors have demonstrated that chemotherapy can alter the molecular makeup of tumors over time by creating shifts in the mutational spectrum.

E.g. Glioblastoma treatment with Temozolomide can enrich for transition of mutations in MMR genes, leading to the development of hypermutated phenotype.

iii) Heterogeneity at a Single Disease Site

Primary tumors can contain multiple geographically separated, molecularly distinct cellular subpopulations. This can result in:

– An uneven distribution of key molecular alterations across different regions of the tumor;

Clonal dominance of potentially actionable driver mutations within individual regions of breast and oesophageal cancers, and clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma (RCC).

– Spatial heterogeneity in the primary tumor might manifest as the ubiquitous presence of key molecular driver alterations, with unequal distribution of additional molecular alterations;

Uniform distribution of key molecular drivers, including BRAF and NRAS with a heterogeneous distribution of additional somatic mutations.

[Technological advances: mapping the clonal landscape]

- Multiregion sequencing:

This is describes the biopsy of sampling of multiple regions within a single lesion. This is considered as an informative investigational strategy that improves the ability to determine the extent of spatial heterogeneity within an individual tumor.

Sampling spatially distinct tumour regions enables reconstruction of phylogenetic trees and differentiation between truncal (shared) versus branch (subclonal) mutations. Clonal mutations are present in all cancer cells within a tumor early in tumor development and subclonal mutations are found in only subset of cancer cells, indicating that they occur later in tumor development. - Single-cell sequencing:

Our ability to characterise and monitor heterogeneity has been transformed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. Single-cell sequencing is a novel technology that enables the isolation and characterisation of individual cells within a mixed population. For example, whole genome sequencing of a single glioblastoma cell have shown the existence of single-cell level variations in EGFR copy number. The single-cell sequencing technique has shown that a substantial level of genetic diversity exists between individual cancer cells but quantifying the extent of heterogeneity at the single-cell level could also provide insight into potential clinical benefits of genotype-guided therapies.

E.g. With T790M-targeting EGFR-tryosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), the therapeutic benefit was proportional to the fraction of cells harbouring the alteration. - Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA):

The unidirectional flow from the primary tumors to metastatic sites is not a universal scenario since many studies suggest that recolonization of the primary tumor happens through circulating tumor cells and exchange of tumor material between different metastatic sites (cross-metastatic seeding).

As a method to monitor tumour burden and detect emergent resistance mutations longitudinally, liquid biopsies or analysing ctDNA emerged as a sensitive and highly informative method as a non-invasive way to monitor heterogeneity. (E.g. serial profiling of plasma samples throughout therapy treatment).

[Two distinct evolutionary pathways and emergence of resistance]

Figure 3 | Resistance arises from two distinct evolutionary pathways.

Dagogo-Jack, I. & Shaw, A. T. (2017) Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies

Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166

a | Outgrowth of pre-existing treatment-resistant clones (red) during treatment.

b | Alternatively, drug-tolerant ‘persister’ cells (blue with orange stripes) that survive initial treatment acquire additional alterations (red or green) that confer resistance to therapy.

Genomic complexity may increase with exposure to targeted therapies. Resistance can arise through many different mechanisms, including acquired mutations, activation of bypass signalling pathways, and cell-lineage changes.

Although the resistance alterations are often thought of as ‘acquired’, several studies suggest that there are de novo resistance alterations that are present at low variant allele frequencies in pretreatment tumor specimens. In the findings of preclinical cellular barcoding experiments, this confirmed that resistant clones often emerge from the selective expansion of pre-existing populations during treatment with targeted agents.

Acquired resistance to antineoplastic treatment is often attributed to:

(i) Selective expansion of pre-existing subclonal populations.

(ii) De novo generation of resistance alterations due to ongoing evolution of drug-tolerant cells = “Persister cells”.

A single genetic snapshot depicted in a diagnostic biopsy sample might become outdated during clinical course, longitudinal sampling is thought to provide an insight into temporal heterogeneity. However, since serial biopsy is unlikely to be practically feasible, there are strategies taht are developed to target the minimal residual disease state (i.e. via ctDNA).

[Future directions – overcoming resistance in heterogenous tumors]

Drug-tolerant cells can develop a wide range of resistance mechanisms. Therefore, targeting this population offers another opportunity to curtail intratumour heterogeneity. Also, a fuel for relapse (persister cells which diversity increases throughout cancer progression) can be present at the earliest stages of tumorigenesis, which highlights the necessity to address the residual disease state and tracking the mergence of treatment-resistant subclones. In conclusion, determining the full extent of tumor heterogeneity given the complexity of cancer and evolution is one of the next important task to effectively develop and select therapies that can prevent or to overcome resistance and designing more effective and durable anticancer therapies.

Leave a comment