I believe the 2019 paper by Neftel et al. is one of the most significant journals not only in terms of glioblastoma (GBM), but more importantly, as a broader paradigm for understanding cellular heterogeneity and plasticity in cancer. The study highlights the power of single-cell transcriptomics in decoding the complexity of cancer and proposes new perspective in interpreting bulk data in relation to “cellular states”.

In fact, these concepts have become central to how scientists – especially those working in pediatric/adult brain tumors – frame discussions around tumor heterogeneity and cell state transitions. This blog introduces the key findings of Neftel et al. and discusses why this work represents a critical foundation for building mechanistic insights into GBM.

Overview

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive form of primary brain cancer which remains incurable despite the long history of research and therapeutic attempts. In the paper, GBM is defined as isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-wild type, and one of the main challenges underlying therapeutic failure lies in their complex heterogeneity – at both genetic and cellular levels. In their 2019 Cell publication, Neftel et al. states that there are two main layers of heterogeneity:

- Reflected by previously established transcriptional subtypes (TCGA subtypes).

Based on bulk-expression profiles, studies of inter-tumor heterogeneity suggests that at least three different subtypes of glioblastoma exist, including proneural (TCGA-PN), classical (TCGA-CL), and mesenchymal (TCGA-MES).

These subtypes are expression-based subtypes since each are typically enriched for selected genetic events (e.g. PDGFRA alterations more common in TCGA-PN and EGFR more common in TCGA-CL glioblastoma).

Multi-region sampling has shown that multiple subtypes can co-exist in different regions of the same tumor – longitudinal analysis also demonstrated that subtypes can change over time and through therapy, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) indicated that distinct cells in the same tumor recapitulate programs from distinct subtypes. - Developmental state of glioblastoma cells in the tumor.

Glioblastoma hijacks mechanism of neural development and contains subsets of GSCs that are thought to represent its driving force, possess tumor-propagating potential, and exhibit preferential resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapies.

Although various markers can enrich for putative GSCs, it is unknown whether different GSC markers isolate distinct or similar cellular states and whether different subpopulations of GSCs give rise to glioblastoma of comparable or diverse cellular composition. It still remains challenging to uncover the mechanism behind glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) biology, such as to what extent is unidirectional hierarchies or reversible state transitions govern GBM.

Neftel et al. therefore presents a comprehensive and integrative framework that unifies cellular diversity, lineage plasticity, and genetic drivers in GBM. Leveraging single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) in 28 tumors (20 adult and 8 pediatric GBM) as well as lineage tracing, and data integration from 401 bulk GBM specimens from the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the authors redefine our understanding of GBM intratumoral complexity.

Four Distinct Cellular States Define GBM Malignancy

Using full-length scRNA-seq (SMART-Seq2), Neftel et al. identified four core malignant cellular states that underlie GBM heterogeneity and also showed that specific genetic alterations bias toward certain cell states from 28 fresh tumor samples:

1. Neural Progenitor-like (NPC-like) state -> CDK4 amplification

2. Oligodendrocyte Precursor-like (OPC-like) state -> PDGFRA amplification

3. Astrocyte-like (AC-like) state -> EGFR amplification

4. Mesenchymal-like (MES-like) -> NF1 loss

To focus on malignant cells, several layers of sorting were done prior to analysis:

– Profiled primarily CD45- cells (CD45: pan-immune marker) / Excluded immune cells (CD45+)

– Inferred copy number alterations (CNAs) on the basis of the average expression of 1000 genes in each chromosomal region; identified large-scale amplifications and deletions. This included chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss – a hallmark of adult GBM (not pediatric GBM).

– High expression of expression of gene sets corresponding to sets of marker genes for oligodendrocytes, T cells, and macrophages with lack of CNAs were excluded (referring to TSNE)

Interestingly, these genotype-driven biases also correspond with the well-known TCGA subtypes (mentioned above) – robust gene expression-based molecular classification of GBM:

- Classical -> AC-like/EGFR

- Proneural -> NPC-/OPC-like (PDGFRA/CDK4)

- Mesenchymal -> MES-like/NF1

One of the most significant insights from this study is that GBM cells are not locked onto a single fixed state but is highly plastic. scRNA-seq is an important technique which has emerged in the recent years to comprehensively characterise cellular states within tissues at a single-cell level.

Malignant cells intra-tumoral heterogeneity is dominated by a few expression meta-modules

In scRNA-seq analysis, a ‘meta module’ refers to a group of genes that exhibit similar expression patterns across a set of cells, often representing a recurring biological process or cell state – identified by clustering:

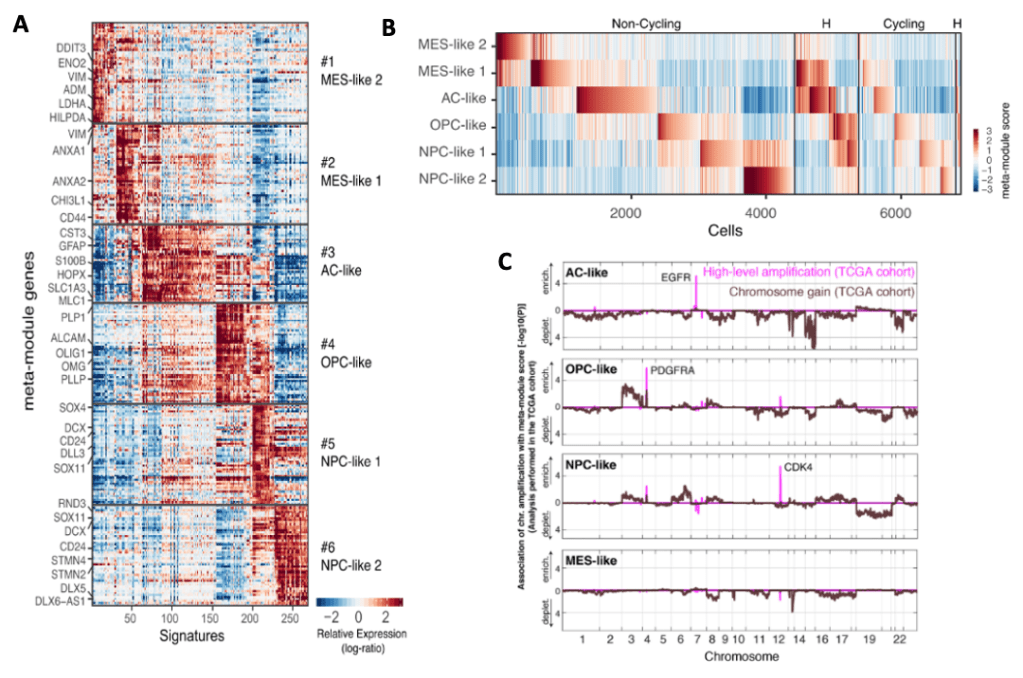

Expression signatures of intra-tumoral heterogeneity among malignant cells.

(A) Meta-modules composed of genes consistently upregulated in potential clusters of the same group.

Six meta-modules consisting of 39-50 genes that highly recur across overlapping signatures from multiple tumors and each meta-module was derived from at least 6 tumors.

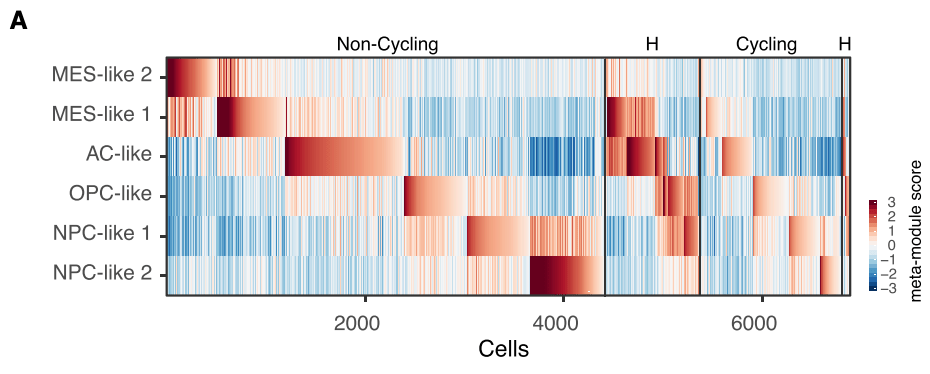

(B) Classification of cells from tumors by expression of the meta-modules and cell cycle programs.

Between 3% and 51% of the cells in each tumor were identified as cycling on the basis of the expression of cell cycle signatures. Cycling cells were enriched in the OPC-like and NPC0-like states, particularly in pediatric tumors.

* This is consistent with proliferation of normal OPC and neural precursors, and with our previous observations in IDH mutant and H3K27M mutant glioma, which are driven by proliferating NPC-like and OPC-like cells.

* However, in glioblastoma, unlike in other classes of gliomas, the other cellular states—AC-like and MES-like—also contain considerable subsets of proliferating cells, possibly reflecting its very aggressive nature.

(C) The distribution of glioblastoma cellular states is associated with chromosomal amplifications across the TCGA glioblastoma cohort. Analysis of the TCGA glioblastoma cohort shows that high-level amplifications of EGFR, PDGFRA, and CDK4 are associated with high bulk scores for the AClike, OPC-like, and NPC-like cellular states, respectively. Single chromosome gains are distinguished from high-level amplifications (Brennan et al., 2013), which are found to have significant associations with three cellular states (AC-like, OPC-like, and NPC-like), whereas no associations of chromosomal amplifications were found with the MES-like state.

Neftel et al. hypothesised that specific cellular states are enriched in tumor subtypes which could be uncovered by single-cell analysis to search for genes that correlate with high frequency in each state but not themselves are a part of expression program of that state. This analysis identified 22 genes that were consistently higher in AC-high tumors than in AC-low tumors. Also, the highest upregulation in AC-high tumor was EGFR. Similar analysis was done for OPC-like, NPC-like, and MES-like states – which defined genetic drivers that influence the distribution of each cellular states.

Even though malignant cells varied considerably between tumors and patients compared to non-malignant cells, meta-modules identified that intra-tumoral heterogeneity in GBM largely corresponds to the four cellular states similarly across different tumors in both adult and pediatric. Most importantly, the meta-modules have been found to mimic developmental cell types but exhibits important distortions from normal programs, hence their notation “-like”. Neftel et al. concludes that through analysing meta-modules we can state “GBM cells span across four different cellular states and their intermediate hybrids, each with proliferative potential, but with higher proliferation of NPC-like and OPC-like states.

Interestingly, although most glioblastoma cells corresponded primarily to one of the four states, 15% of the cells highly expressed two distinct meta-modules and hence were defined as ‘‘hybrid’’ states. Therefore, it is important to realise that each of the tumors contain cells in at least two of the four cellular states, with most tumors containing all four states (denoted as “H” below):

Assignment of malignant cells to cellular states and their hybrids: The heatmap shows he meta-module scores of all non-cycling cells (left) and cycling cells (right). Within each group, the cells are ordered by their maximal score, for cells mapping to one meta-module, followed by cells mapping to two meta-modules (hybrid states, denoted as ‘‘H’’).

In conclusion, Neftel et al. have elucidated the spectrum of expression states of glioblastoma cells and their plasticity, identifying cellular programs that recapitulate neural development, cell cycle, and influences of the microenvironment. By showing that specific genetic drivers of glioblastoma influence the frequency of those states, Neftel et al. also provide a cellular correlate to glioblastoma genetic heterogeneity and a model that explains why different bulk expression programs, such as the TCGA subtypes, are enriched for defined genetic alterations. Lastly, they also demonstrate cellular plasticity via combining scRNA-seq and cellular barcoding techniques.

Leave a comment