Published in 2021, the fifth edition of the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System highlights the role of advances in novel molecular profiling approaches in identifying new CNS tumor types and subtypes.

The changes in CNS tumor classification have been impacted by the improvements in novel diagnostic technologies and the recommendations of the Consortium to Inform Molecular and Practical Approaches to CNS Tumor Taxonomy (clMPACT-NOW).

Developing on from the fourth edition in 2016, where nucleic acid-based methodologies* clearly contributed towards a shift in CNS tumor classification and diagnosis, the fifth CNS WHO Classification (WHO CNS5) incorporates the powerful impact of recent emergence of DNA methylome profiling* into the classification system.

* Nucleic acid-based methodologies include DNA and RNA sequencing, RNA expression profiling, DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, etc.

* DNA Methylome profiling is the use of arrays to determine the pattern of DNA methylation across the genome.

Most CNS tumor types can be reliably identified by their methylome profiling, and WHO CNS5 recognises the families of pediatric-type diffuse gliomas (both high-grade and low-grade) for the first time, highlighting the pathobiology underlying gliomas arising primarily in children and young adults.

This post will focus on and give you an overview of the family of pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas, especially the as this is my primary area of research at the moment.

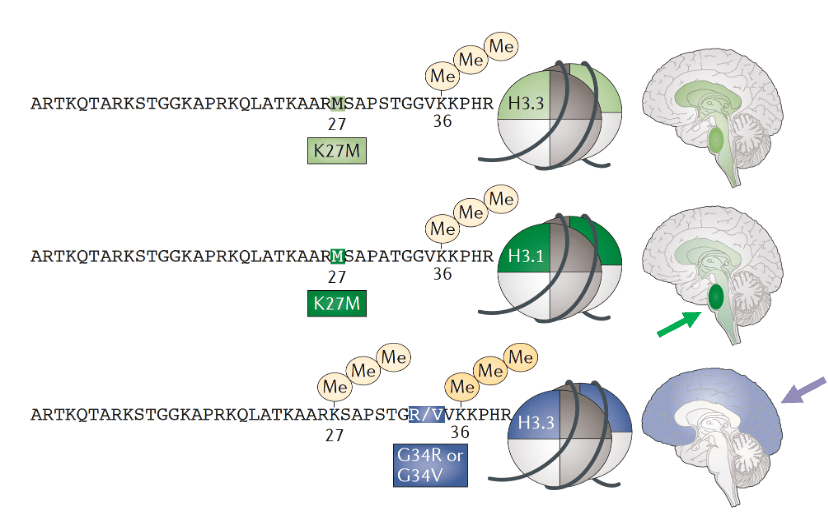

In children, following leukaemia, which is the most frequent type of cancer in children, brain cancer is the next predominant malignancies. The WHO CNS5 classifies Pediatric-type Diffuse High-Grade Gliomas (pHGG) into four subtypes. The first two subtypes are characterised by somatic mutations in histone tails: H3 K27-altered and H3 G34-mutants. These substitutions are known to occur in genes encoding either histone H3.1 or H3.3 and both histone H3 mutations lead to a reduction in DNA methylation (more in G34 than K27) throughout the epigenome and therefore promotes gene transcription.

1. Diffuse Midline Gliomas (DMGs)

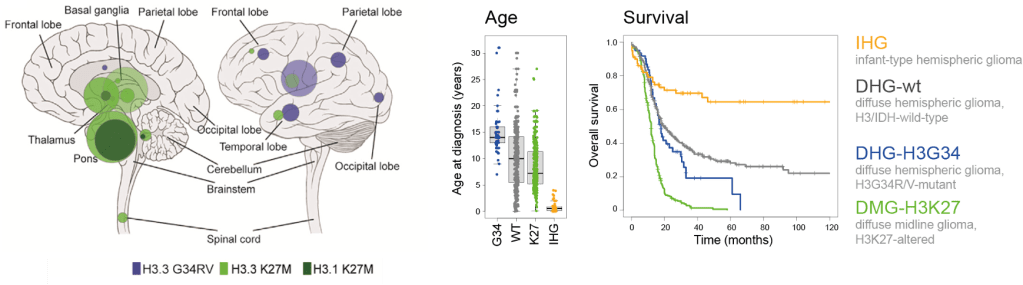

DMGs are H3 K27-altered tumors which have a Lysine to Methionine substitution at position 27 and are typically found throughout the midline structures including the thalamus and the brainstem, including the pons. They usually arise in children with an earlier onset at age mostly between 5-7 years. The prognosis remains very poor, with a two-year survival of less than 10% (survival curve below – green).

DMGs are recognised as a CNS WHO grade 4 malignancy regardless of histological features and it is characterised by the loss of H3K27me3, molecularly defined into three subtypes:

i) H3.1 or H3.3 K27M mutation

– The mutation of the H3-3A leads to an amino acid substitution of lysine (K) to methionine (M), or rarely to isoleucine (I), affects the enzymatic activity of a subunit of Polycomb Repressive complex 2 (PRC2) called EZH2 (involved in gene silencing), and ultimately causes an extensive loss of H3K27me3.

In other words, K27M mutation confers loss of transcriptionally repressive trimethyl mark at lysine 27 on histone H3, which can be easily detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

ii) H3-WT with EZH Inhibitory Protein (EZHIP) overexpression

– EZHIP is a protein that regulates PRC2 complex, which often mimics the effects of the H3.1 K27M oncohistone mutation, leading to inhibition of PRC2 activity and a loss of H3K27 trimethylation.

– This mechanism is also often found in posterior fossa A (PFA) ependymoma.

iii) Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) alteration – either mutation or amplification

– A study identified that bi-thalamic H3-WT tumors often harboured EGFR mutations.

2. Diffuse Hemispheric Gliomas (DHGs)

DHGs are H3 G34 mutant tumors which have a glycine to valine or arginine substitution at position 34 and they arise in the cerebral hemispheres. They occur most frequently in adolescents and young adults with median age of 15.8 years. They have a slightly better survival compared to the K27-altered pHGGs (survival curve below – blue).

Landscape of Pediatric-Type Diffuse High-Grade Gliomas: Distinct age, Locations, Clinical Outcomes, Biology, and Therapeutic Targets

Mackay et al., 2017, Cancer Cell

The other two subtypes, Diffuse Pediatric High-Grade Glioma H3 (DHG-wt) and IDH-wildtype (IHG) and Infant-type Hemispheric Glioma also have distinct characteristics:

3. IHG

IHG typically occurs in very young children, usually under the age of 1 for methylation-defined IHG patients. These tumors are primarily found in cerebral hemispheres of the brain and are often driven by specific gene fusions, and receptor tyrosine kinase alterations such as gene fusions in NTRK family, ALK, ROS1, and MET1. They have a better overall survival than other pHGGs with around 54% surviving more than five years (survival curve above – yellow).

4. DHG-wt

Unlike IHG, DHG-wt can occur across a range of pediatric ages and can also be seen in older children and adolescents. They also arise typically in cerebral hemispheres and they lack H3 mutations. They are often driven by different oncogenic pathways such as TP53, PDGFRA, EGFR alterations, and MYCN amplifications. They usually have a poor prognosis with median survival of 17.2 months (survival curve above – grey).

Despite the defined subclassification of pHGGs based on histone H3 mutations, it is important to realise that more than half of all childhood diffuse infiltrating gliomas do not fall into these categories!!

Some examples include:

- 5 – 10% of predominantly cortical tumors harbour activating BRAF600E mutations.

- <5% harbour hotspot mutations in the IDH1/2 genes associated with global hypermethylayion (“G-CIMP”).

Whilst MGMT hypermethylation is one of the markers of adult glioblastoma, this is not as relevant in children. This is important to note since this is highly relevant to why the current Standard of Care (SoC) – surgical resection followed by radiotherapy/chemotherapy (temozlomide) – for brain tumors is not effective on children with DMGs, leading to extremely poor clinical outcome. Note: This SoC is still used in hemispheric tumors, with some utility.

To provide you with a brief background of the above, MGMT gene encodes a DNA repair enzyme which transfers the alkyl group from the O6 position of guanine to itself. This subsequently irreversibly inactivates the enzyme and is marked for degradation via ubiquitination (hence “suicide enzyme”).

However, hypermethylation of CpG islands in the MGMT gene promoter region leads to epigenetic silencing of the MGMT gene, resulting in reduced transcription and loss of MGMT protein expression. This loss of MGMT protein expression results in loss of DNA repair capacity and accumulation of alkyl groups. This allows alkylating agents such as temozolomide to exert greater cytotoxic effects in tumors with MGMT promoter hypermethylation.

Since recent advances in molecular profiling techniques allowed us to discover that paediatric gliomas have different molecular pathological features from adult glioblastoma, this has shifted the paradigm of paediatric brain cancer research in the direction of examining epigenetic features of pHGG patients. The glioma team and I are currently investigating ways to translate basic molecular pathology findings into improved clinical outcomes for children with diffuse-type diffuse high-grade gliomas.

Further information can be found in the paper “Pediatric high-grade glioma: biologically and clinically in need of new thinking” (Jones et al., 2017, Neuro-Oncology). This is the link for my NOTES!

Leave a comment